I’m picky about the fantasy stories I like, but I love J.R.R. Tolkien’s work. He did such a effective job in his world-building that I suspend my disbelief. His Middle Earth stories feel like reading history.

As a young man Tolkien began creating a couple new languages, and then he began writing poems and stories for the elves who would speak these languages. Many years later he wrote a children’s story set in this fictional world, yet in a much later time period than his earlier stories were set.

That children’s story was The Hobbit. It became so popular that Tolkien’s publisher requested he write a sequel.

Tolkien got to work. However, what he turned in was not The Hobbit sequel that was requested, but The Lord of the Rings. Many of us readers consider The LOTR to be a sequel to The Hobbit, but Tolkien considered it to be a continuation of his stories about the First Age.

His son, Christopher, later released these stories as The Silmarillion. (My edition of LOTR has some of this history included as back matter. Do all editions?)

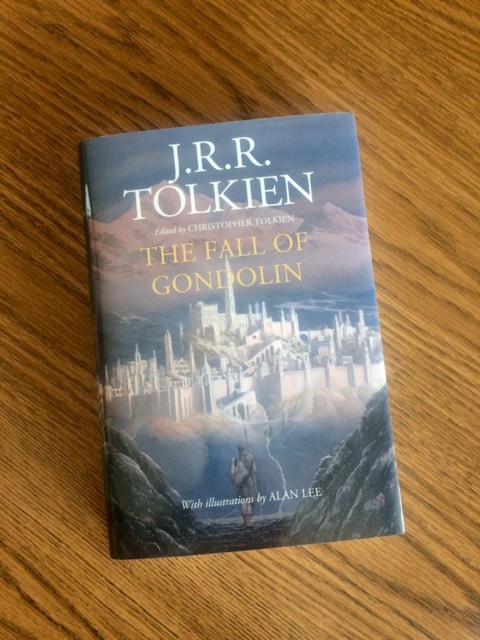

Christopher has edited and released many of Tolkien’s works in recent years. The latest book, The Fall of Gondolin, was published in 2018.

All this to say, that when I read The LOTR, I was reading a story that had thousands and thousands of years of history to it. Some of the characters refer to past places and events and kingdoms that were still affecting the current narrative.

In addition, The LOTR, The Silmarillion, and The Fall of Gondolin seems like reading history because of the language. The vocabulary is expansive and challenging. The syntax often has a formal and old-fashioned feel.

It’s like I’m reading something written hundreds of years ago.

That’s totally different than reading some historical fiction written in the Twenty-first Century.

I don’t want to be too critical of modern historical fiction. Authors are told to avoid dialects, slang, obscure language in order to be accessible to the modern reader—especially child readers.

I understand and agree with that.

I find Shakespeare to be difficult to read, and his works are only about 500 years old. Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, just over 600 years old, are totally inaccessible to me unless they have been translated into modern, or somewhat modern, English.

Yet a story written in Twenty-First Century English with only a sprinkling of historical vocabulary might sound so modern that it doesn’t feel historical at all.

I prefer historical stories to land in the middle of the language continuum—neither so obscure that I can’t understand it, nor so modern that it sounds like the dialogue is spoken by contemporary speakers. (There are many modern historical fiction that are good examples of this. Last month I wrote about Full of Beans by Jennifer L. Holm that feels like it’s truly set in the 1930s because of the vocabulary the characters used.)

I find that Tolkien’s writing, although challenging, is also delightful and gives an added sense of history to his stories. The stories feel real.

What makes a story feel historical to you? The vocabulary? Setting? Something else? Are you a Tolkien fan? Have you read The Fall of Gondolin? What did you think?