I’m on a multi-year quest to read and blog about all the winners of the Scott O’Dell Award for Historical Fiction. I don’t do a traditional review. Instead I write about the history and writing craft lessons I learn.

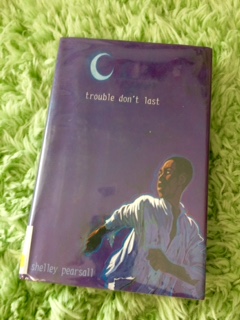

This month I read the 2003 winner, Trouble Don’t Last by Shelley Pearsall.

This middle grade novel begins in 1859 Kentucky and features Samuel, an 11-year-old slave boy, who runs away with an aged slave, Harrison, who doesn’t always seem to have all his wits about him.

Writing Lesson:

POV (Point of View)—Pearsall wrote this novel in 1st Person which allows the readers to experience the story from the main character’s point of view. As I was reading this book I found myself frustrated with Samuel’s childishness. He’s a bundle of excessive fear, and at one point he nearly gives away his and Samuel’s hiding place.

Then I remembered Samuel is a child—one without parents, who has known hardship and cruelty, and who has never been away from the only home he knows.

Pearsall did a very good job portraying what a boy in Samuel’s position might have experienced—including his emotional reactions. She also captured Samuel’s childlike wonder in terms that he would’ve used. For example, the first time he sees a steam train he doesn’t compare it to ships or wagons. I love how he describes it:

“Coming across the field in front of us was an enormous black cookstove, big as a house. Black smoke poured from its wide chimney….Behind the stove came a whole line of houses and sheds, flying on wheels.”

Samuel in Trouble Don’t Last

History Lesson:

Human nature–As I was reading Trouble Don’t Last, I was struck by the variety of people who help Samuel and Harrison: black, white, religious, non-religious, educated, and laborers. They helped for a variety of reasons, some selfless and some self-serving. But all those people helped, even though they were risking serious repercussions. Why?

This book is a good example of why historical fiction remains relevant. It’s not just stories about people who lived unrelatable lives a long time ago. Yes, times change, and events, beliefs, and technology are different. But we humans and our nature are the same as in the past.

We still have the capacity to love, hate, aid, hurt, seek revenge, and offer forgiveness, etc. We still choose to do right and choose to do wrong, often at the same time.

I believe historical fiction helps us understand past events and people, but it also helps us understand ourselves. And sometimes it’s easier to understand ourselves when we’re looking at someone else.

For more info:

Previous posts about Scott O’Dell Award winners

Have you read Trouble Don’t Last? How about other books that have done an excellent job at letting you experience a child character’s point of view? What have you read that helped you understand yourself?